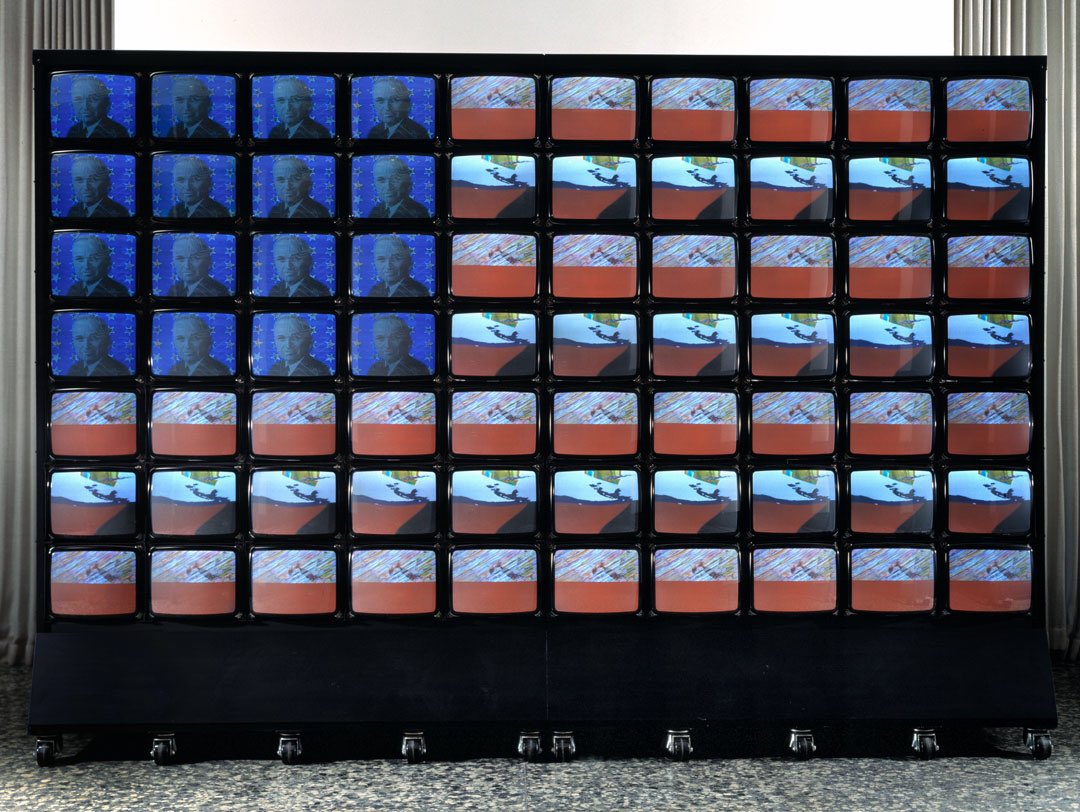

Paik’s work offers a vision of technologized humanity, a guide to navigating the “cybernated life” he perceived to be imminent. Like many of his peers, Paik often claimed to be humanizing technology, but the inverse-a far weirder prospect-might also be true. Paik has been described as the “father of video art,” but the medium-specific moniker obscures his broader fascination with how technologies alter our bodies and our perceptions.

Where Cage “prepared” pianos for open-ended compositions, Paik applied a magnet to a television set to create distortion effects and eventually sought to bring the aleatory methodology to broadcast television. At the same time, it’s important not to let the Cage myth obscure the significance of Paik’s fundamental innovation: translating neo-avant-garde aesthetics of chance and indeterminacy from the rarified world of modernist music into the realm of mass media, a process that accelerated once Paik moved to New York in 1964. It would be hard to overstate the influence of Cage’s experimentalist ethos on Paik’s work, and the exhibition might have gone deeper into the relationship between these two seminal Buddhist artists.

Born in Korea in 1932, Paik spent most of his life outside his native country, studying art and music in Japan before moving in 1956 to Germany, where he studied with Karlheinz Stockhausen, participated in early Fluxus events and met John Cage.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)